Victorian Era (1837 - 1901)

The Victorian era is the period of the reign of Queen Victoria from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. During the Victorian era, the British economy flourished. The Industrial Revolution meant substantial technological progress and made Great Britain a forerunner for a considerable time. Furthermore, it was a peaceful time in Europe. Queen Victoria had little political power or influence but the domestic policy managed to keep everything stable. However, the international policies and colonialism of the British Empire were anything but peaceful.

The changing work culture of this post-industrial revolution time meant that people (at least those not working in factories) had leisure hours and could partake in popular forms of entertainment. Education levels rose through a more formalised school system which in turn benefitted literature, theatre, galleries, music venues and the opera houses.

The Victorian Era saw fashion chance, sometimes dramatically, every couple of years. From wide, bell-shaped skirts over the crinoline to figure hugging styles in the 1870s, there is a lot of variety comprised within the generalising name 'Victorian Era'. The making of clothes and dress culture changed massively during the industrial revolution which introduced the sewing machine, mechanical weaving, and therefore made ready-made clothing possible. This overturned the entire textile industry and lastingly changed society. The rise of the middle class during the era had a formative effect on this time, brought on by the growing wealth that the industrial revolution made possible.

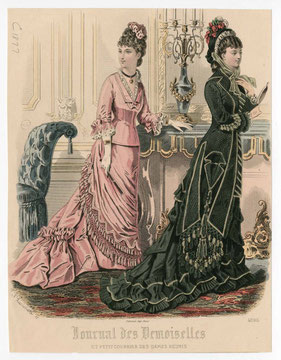

The Victorian era was the heyday of fashion magazines. Print, materials and technologies had become more affordable and literacy levels were up across societies. Disposable income had risen (for some) during the industrial evolution. Magazines such as Harpers Bazaar and the Journal des Demoiselles testify to this prolific output of fashion prints. These prints circulated in society, they were shared and discussed. Women ordered from the makers advertising in the magazines or took the prints as inspirations to the dressmakers of their choice. Fashion was becoming more democratic, but also somewhat more uniform by the means of mass production.

The 1820's and 30's are a fascinating time, sandwiched between the Regency and the onset of Victorian fashion.

Towards the end of the Regency/Empire epoch (approx. 1820), the high empire waist began slipping down about an inch every year. Therefore existing gowns were altered according to the new fashion with wide waistbands to help lowering it.

In the mid-twenties, the waist reached its natural position and it became again fashionable to be very slim. Consequently, corsets were worn again. The wasp-waist was contrasted with increasingly full but sometimes only ankle-long skirts (sometimes even padded with animal hair to give them shape) and the little puffed sleeves of the early 1820s gave way to the so called “leg-o-mutton” sleeves. Those sleeves, most popular in the mid 30s, needed to be supported by padding worn as underwear or enhanced with boning and were therefore very hindering. A higher neckline was in vogue now. The new fashionable silhouette was: broad shoulders through the sleeves, a very slim waist and a full skirt. Evening and ball gowns stayed low-cut and short-sleeved. After the fashion of pure white and pastel shades, a change has been taking place and clothes became noticeably colourful and decorated. In the 1830s, chintz, a printed cotton fabric of Chinese origin came into fashion.

In this time, the Romantic Movement had reached its zenith: The Romantic fiction and historical novels and plays were loved very much by a great readership. As a consequence, the ladies (with a quixotic view of the past centuries, especially the Middle Ages and the Elizabethan Era) wanted to dress like the work's heroines, so that for instance (small) Elizabethan ruffs were seen again. In Germany, this time is called Biedermeier.

During the Victorian era, it was custom to change one's dress several times a day, at least once in the late morning and once before dinner. There were different dresses for different parts of the day and different activities. The option to buy cheaper clothes made this vast variety possible, although only to women of a certain income level. There was the the dressing gown, the morning dress, the day dress to receive visitors, the visiting dress to go visit, the afternoon dress, the walking costume, the carriage dress (ensemble for drives in open carriages, riding habits, dinner & evening toilette, ball gowns and the Full-Dress toilette for very formal occasions at court.

In the 1840s, the huge leg-o-mutton sleeves vanished to be supplanted by tight-fitting ones. The skirts became even wider, supported by crinolines. Crin, French for horse hair, gave this undergarment it's name: the crinoline is a bell shaped hoop-skirt, at first stiffened with horse hair, later normally made of steel rings and fastened around the waist with bands.

Evening gowns had a low, wide neckline and small close-fitting sleeves. Shiny, glimmering fabrics like silk and taffeta were the thing, just as lace in form of trimming along the neckline, as gloves and stoles.

The waist appears so small through optical illusion: the very wide skirt and the bodice that is padded and cut to enhance the shoulders by big sleeves, ruffles and a wide neckline form a contrast to the waist that makes it appear extra slim. It is not necessarily the work of lacing a corset very tight.

By the 1850s, a crinoline made of steel rings made it possible to reach a great size of skirt without

using so many petticoats. To sit down or pass a narrow doorway the wearer could just lift the rings of the hoopskirt on one side. Crinolines look very static and imposing but the steel

rings connected by ribbons make them highly flexible.

Evening gowns had a rather low neckline and were worn off the shoulders or just on the shoulders. Skirts with many layers of fabric creating horizontal valances were very fashionable. This flouncy style supported the bell-shape and width of the skirt even more. Although Victorian fashion looks very ornate and difficult, wearing it and getting dressed in it are no hours-long processes or hardships. Put on your chemise and drawers and stockings with garters, your corset, your skirt(s) and your bodice and voila, you are dressed!

By the late 1850s and early 1860s

the crinoline had reached an enormous measure. In the early 1960s, the skirts became increasingly flatter in the front but flared out into a conical shape towards the back until in the

later 1860s they became rather triangular in silhouette.

The immense amounts of fabric required for this fashion was costly, even when choosing a reasonably affordable cloth. To save on material costs, several matching bodices were made to go with the huge skirts. This meant that one skirt had a matching day bodice which a high neckline and long sleeves (or several) and one or more short-sleeved and lower cut bodices with varying degrees of fine trim to attend dinners and parties or go to the opera.

For hot summer days, the Tarlatan, a very light flowing dress, made the heat more enjoyable. It was made of light cotton in linen weave, being both light and strong. Normally white, they were a thankful base for colourful ribbon trimming or frills. Claude Monet wonderfully portrayed the Tarlatan dresses and their nature in his painting "Women in the garden", 1866.

Do you Wish to own or gift a true piece of history?

By the end of the 1860s, the crinoline was replaced by the bustle. The silhouette was no longer bell-shaped but strait in front and projecting in the back behind the seat. This bustle style stayed until the 1770s before briefly vanishing for a super fitted, more natural look before coming back for the Second Bustle Era in around 1882.

Either a cage bustle as in the picture was used, or bustle pads (padded pillows tied around the waist that sat in the back to give the skirts that volume and drama). During the bustle era, the dresses also consisted of two pieces: the skirt and the jacket-style bodice. The skirt with its bustles and pleats was decorated to the minutest detail with all sorts of lavish embellishment.

In around 1874, the first bustle era concluded for the sake of a very slim and figure-hugging silhouette. The skirts are now very narrow and the undergarments are very limited and fitted for the so called 'natural form'. The cut of the bodice is lengthened well down to over the hips to create this smooth look. The skirts are usually decorated with ruffles, ruches, lace, tassels and silk flowers. They can end in a train or be floor long for more ease of walking.

The shoulders are very narrow with tight-fitting sleeves and even the hairstyles are now high to support this slim and pillar-like silhouette. This style, however, lasted only until about 1882 when the bustle returned and the skirts once more became wide at the back.

The Second Bustle Era of the 1880s creates an almost architectural style with skirts that are round but very flat at the front while they protrude at the back. Take a look at George Seurat's "A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte", 1884 - 1886, for an

extreme and stylised depiction of this style.

From 1884 onwards till 1914, this epoch is also called fin de siècle or Belle Époche, in the US it is the Gilded

Age.

The decorative arts during the fin de siècle are chiefly dominated by the Art Nouveau movement. In the 1880s and 1890s, artistic influences came from Japan into European art and fashion. Japanese art was highly influential on the Art Nouveau Movement due to its clarity of line and natural themes. The chrysanthemum, for example, had been brought to Europe and enjoyed great popularity in embroidery.

Sleeves were usually voluminous at the shoulders and skirts were bell-shaped and flowing.

The S-curve with a large pigeon breast (also called mono-bosom) was achieved through layers of

ruffled corset covers and blouses. It was not necessarily the body that was forced in an unnatural shape and rather the clothes that were styled and adapted to give that look.

Elements of Victorian era fashion survived until today: Based on Victorian styles (or clichés) are e.g. the Steampunk and Lolita movement.

Read more about the lives of Victorian women in my blog:

Hair:

The hairstyles had become ever more extravagant throughout the 1820s and 1830s. Especially in the 1830s, hairstyles in fashion magazines

are veritable confections defying gravity in their sculptural arrangement and decorated with twigs of silk flowers, leaves and pearls. The top hair was arranged into high up-dos while the side

hair was curled (or naturally curly) and left to frame the face. Wire supports, hair rats (padded hairpieces to add volume under the hair) as well as clip in hairpieces were needed for the

hairstyles.

In the 1840s, the hair became much simpler. It was parted in the middle and swept back into a bun/up-do behind the head, thus framing the face (see most adaptations of Jane Eyre, for example). The hair sleek, straight and parted in the middle. The hairstyles would remain relatively simple from then on, as a sleek style swept back into a braided bun or hairnet, or as a bun combined with corkscrew curls around the face. From the 1870s onwards, as the narrow bustle style highlights the vertical axis, the hair followed dress styles and was arranged as an up-do on the top of the head and framing the face.

Accessories:

Folding fans, decorated with painted scenes were an important accessory. Smelling salts were carried in small scent bottles,

as well as pocket watches and whole belt chatelaines with a thimble, small scissors, button hooks and trinkets all on little chains. For middle- and upper class women, protecting the complexion

from a sun tan meant that gloves and parasols remained as important as they had been in the Regency and before.

For decorative purposes, modesty and for protection from draughts, shawls, lace capes such as that of the Comtesse de La Tour-Maubourg, neckerchiefs and other fashionable stoles were worn.

The later 19th century is marked by social shifts which gave women greater freedoms. In a post-industrial revolution era,

clothes and accessories had to be especially practical for women working in factories or in the newly popular department stores. Exercise for the purposes of health became increasingly recognised

and integrated into the daily life of those with leisure to undertake sports, such as cycling or playing tennis. Handbags to carry around all necessary items now usually had a metal closure with

a textile pouch bag attached which could be decorated by cross-stitch embroidery or beading.

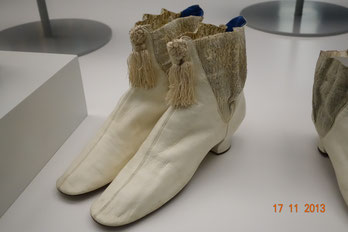

Shoes:

Flat shoes made of soft leather or, for special occasions, silk can be seen in portraits and fashion plates for much of the Victorian era. These flats could either be slipped on or tied with ribbon strapping. They very much resembled Regency footwear.

Wearing heels became more fashionable in the 1870s. The heels were usually not very high and

often curved, such as in this pair in the collection of the Otago Museum in Dunedin, New Zealand. The toes were often round or pointed. In the picture above of this pair of boots at the Otago

Museum Dunedin the triangles at the ankles are made of elastic material so that the boots could easily be pulled on and fitted better. Boots could also be buttoned by many small buttons which

required a button hook (a metal stick with a small hook at one end) to make opening and closing them more efficient.

Your support means a lot to me! I If you wish to make a small, one-off contribution, you can buy me a KO-FI. I appreciate any support immensely and it motivates me to continue maintaining this website and providing free art and culture education!

Patterns:

- Izabela Pitcher (Prior Attire), The Victorian Dressmaker and The Equestrian Dressmaker Books

- Black Snail Patterns

- Burda 2768 (dresses with hoop skirt; Biedermeier)

- Burda 7466 (dresses; Biedermeier)

- Burda 7880 (1888 dress)

- Butterick 4540 (day dress)

- Butterick 5543 (dress)

- Butterick 5696 (bustle dress)

- Butterick 6694 Historical (2 day dresses)

- McCall's 3597 (dresses)

- McCall's 3609 (undergarments including crinoline)

- McCall's 5129 (bonnets)

- Simplicity 1818 (ca. 1850-1860; dresses)

- Simplicity 2172/7532 (Steampunk dresses)

- Simplicity 2881/7320 (reminiscent of Elisabeth 'Sisi', Empress of Austria)

- Simplicity 2887/ 7318 (ca. 1850s)

- Simplicity 2890 (undergarments)

- Simplicity 3727 (dress)

- Simplicity 3855 (dress)

- Simplicity 4400 (dress)

-

Simplicity 4510

- Simplicity 7216 (undergarments including crinoline)

- Simplicity 9764 (undergarments including crinoline)

- Simplicity 9769 (undergarments)

- Please note that this list does claim no completeness and does not operate as advertisement. It was merely composed for informative purposes. Furthermore, no valuation of the patterns is implied or intended -

© Epochs of Fashion

Keywords: Empress Sisi, dress, gown, robe, fashion, Queen, Victoria, hoop, skirt, bell, pattern, simplicity, burda, corset, Princess

Albert de Broglie, fashion plate, Biedermeier, costume, crinoline, log-o-mutton, Victorian, age, era, epoch, underwear, accessories, shoes, boots, Victorian